SUMMARY: The American Cancer Society estimates that for 2022, about 20,050 new cases of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) will be diagnosed in the United States and 11,540 patients will die of the disease. AML can be considered as a group of heterogeneous diseases with different clinical behavior and outcomes. Cytogenetic analysis has been part of routine evaluation when caring for patients with AML. By predicting resistance to therapy, tumor cytogenetics will stratify patients, based on risk and help manage them accordingly. Even though cytotoxic chemotherapy may lead to long term remission and cure in a minority of patients with favorable cytogenetics, patients with high risk features such as unfavorable cytogenetics, molecular abnormalities, prior Myelodysplasia and advanced age, have poor outcomes with conventional chemotherapy alone. AML mainly affects older adults and the median age at diagnosis is 68 years. A significant majority of patients with AML are unable to receive intensive induction chemotherapy due to comorbidities and therefore receive less intensive, noncurative regimens, with poor outcomes.

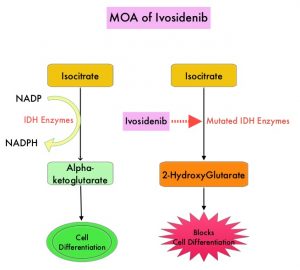

Isocitrate DeHydrogenase (IDH) is a metabolic enzyme that helps generate energy from glucose and other metabolites, by catalyzing the conversion of Isocitrate to Alpha-Ketoglutarate. Alpha-ketoglutarate is required to properly regulate DNA and histone methylation, which in turn is important for gene expression and cellular differentiation. IDH mutations lead to aberrant DNA methylation and altered gene expression thereby preventing cellular differentiation, with resulting immature undifferentiated cells. IDH mutations can thus promote leukemogenesis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and tumorigenesis in solid tumors and can result in inferior outcomes. There are three isoforms of IDH. IDH1 is mainly found in the cytoplasm, as well as in peroxisomes, whereas IDH2 and IDH3 are found in the mitochondria, and are a part of the Krebs cycle. Approximately 20% of patients with AML, 70% of patients with Low-grade Glioma and secondary Glioblastoma, 50% of patients with Chondrosarcoma, 20% of patients with Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, 30% of patients with Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and 8% of patients with Myelodysplastic syndromes/Myeloproliferative neoplasms, are associated with IDH mutations.

TIBSOVO® (Ivosidenib) is a first-in-class, oral, potent, targeted, small-molecule inhibitor of mutant IDH1. The FDA in 2018, approved TIBSOVO® for adult patients with relapsed or refractory AML with a susceptible IDH1 mutation and in 2019 approved TIBSOVO® for newly diagnosed AML with a susceptible IDH1 (Isocitrate DeHydrogenase-1) mutation, in patients who are at least 75 years old or who have comorbidities that preclude the use of intensive induction chemotherapy. VIDAZA® (Azacitidine) is a hypomethylating agent that promotes DNA hypomethylation by inhibiting DNA methyltransferases. VIDAZA® has been shown to significantly improve Overall Survival (OS) when compared to conventional care regimens in elderly unfit patients with newly diagnosed AML, who are not candidates for intensive chemotherapy. In a Phase Ib trial, TIBSOVO® in combination with VIDAZA® showed encouraging clinical activity in newly diagnosed IDH1-mutated AML patients.

AGILE is a global, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, Phase III trial in which the efficacy and safety of a combination of TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® were assessed, as compared with placebo and VIDAZA®, in patients with newly diagnosed IDH1-mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia, who were ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive TIBSOVO® 500 mg orally once daily combined with VIDAZA® 75 mg/m2 subcutaneously or IV for 7 days in 28-day cycles (N=72) or placebo and VIDAZA® (N=74). All the patients were to be treated for a minimum of six cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicities. The median patient age was 76 years, 75% had primary AML and 25% had secondary AML, 67% had intermediate cytogenetic risk and 22% had poor cytogenetic risk. Patients were stratified according to geographic region and disease status (Primary versus Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia). The Primary end point was Event-Free Survival, defined as the time from randomization until treatment failure (failure of complete remission by week 24), relapse from remission, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first.

At a median follow-up of 12.4 months, Event-Free Survival was significantly longer in the TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® group than in the placebo and VIDAZA® group (HR=0.33; P=0.002). This benefit was seen across all key subgroups. The estimated probability that a patient would remain event-free at 12 months was 37% in the TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® group and 12% in the placebo and VIDAZA® group. The median Overall Survival was 24.0 months with TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® and 7.9 months with placebo and VIDAZA® (HR=0.44; P=0.001). Among those patients who were dependent on transfusion of red blood cells, platelets, or both at baseline, a higher percentage of patients converted to transfusion independence with TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA®, than with placebo and VIDAZA® (46% versus 18%; P=0.006). Health-Related Quality of Life scores favored TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® across all subscales. Grade 3 or higher Adverse Events included febrile neutropenia (28% with TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® versus 34% with placebo and VIDAZA®) and neutropenia (27% versus 16%, respectively). Differentiation syndrome of any grade occurred in 14% of the patients receiving TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® versus 8% among those receiving placebo and VIDAZA®.

It was concluded that a combination of TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® significantly improved Event-Free Survival, Response Rates, and Overall Survival, as compared with placebo and VIDAZA®, in patients with newly diagnosed IDH1-mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia, who were ineligible for induction chemotherapy. The authors added that treatment with TIBSOVO® and VIDAZA® resulted in better Quality of Life and higher rates of transfusion independence.

Ivosidenib and Azacitidine in IDH1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Montesinos P, Recher C, Vives S, et al. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1519-1531.