SUMMARY: It is estimated that in the United States, approximately 22,440 women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2017 and a little over 14,000 women will die of the disease. Ovarian cancer ranks fifth in cancer deaths among women, and accounts for more deaths than any other cancer of the female reproductive system. Approximately 75% of the ovarian cancer patients are diagnosed with advanced disease and the 5 year Overall Survival rate is about 20-30%. These patients are often treated with platinum based chemotherapy following primary surgical cytoreduction.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes and functional BRCA proteins that repair damaged DNA and play an important role in maintaining cellular genetic integrity. They regulate cell growth and prevent abnormal cell division and development of malignancy. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 account for about 20 to 25 percent of hereditary breast cancers and about 5 to 10 percent of all breast cancers. They also account for 15 percent of ovarian cancers in addition to other cancers such as colon and prostate.

Homologous Recombination (HR) is an important pathway that allows repair of double-stranded DNA breaks and operates during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, relying on several proteins including BRCA1 and BRCA2. Deficiency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 results in non-functioning HR pathway (HR Deficiency), and other pathways then come in to play, which are less precise and error prone, resulting in the accumulation of additional mutations and chromosomal instability in the cell, with subsequent malignant transformation. Hereditary Epithelial Ovarian Cancer was thought to be caused almost exclusively by mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. It however now appears that about 50% of the high grade serous ovarian cancers have aberrations in HR repair pathway. BRCA mutations can either be inherited (germline) and present in all individual cells or can be acquired and occur exclusively in the tumor cells (somatic). Somatic mutations account for a significant portion of overall BRCA1 and BRCA2 aberrations, and loss of BRCA function due to frequent somatic aberrations in ovarian cancers likely deregulates HR pathway and increases sensitivity to platinum drugs. Majority of the women with germline BRCA mutations (gBRCA) are positive for HR deficiency.

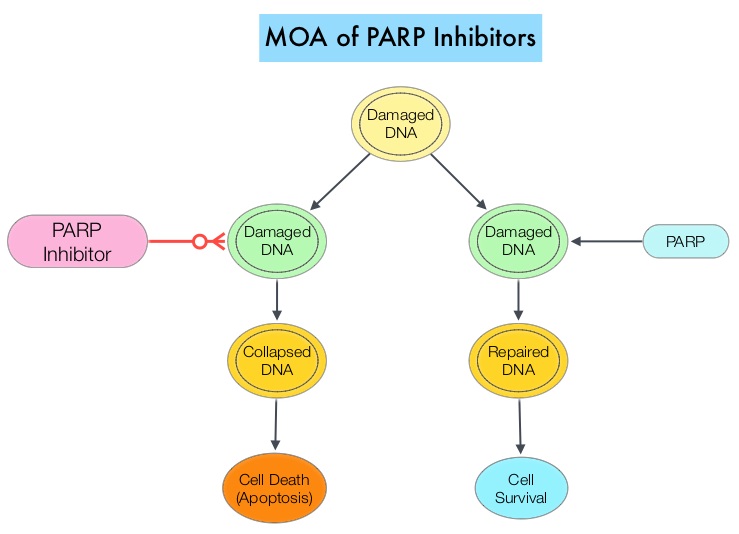

The PARP (Poly ADP Ribose Polymerase) family of enzymes which include PARP1 and PARP2, repair damaged DNA. PARP inhibitors kill tumors defective in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes through the concept of synthetic lethality. Epithelial Ovarian Cancers with Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) have demonstrated sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. The two currently FDA approved PARP inhibitors include LYNPARZA® (Olaparib) for the treatment of ovarian cancer with gBRCA mutations after three lines of therapy and RUBRACA® (Rucaparib) for the treatment of ovarian cancer with gBRCA mutations and /or somatic mutations after two lines of therapy.

Niraparib is a highly selective PARP 1/2 inhibitor, that detects DNA damage and promotes its repair. Previously published studies demonstrated the antitumor activity of Niraparib in patients with ovarian cancer, at a maximum dose of 300 mg per day, with a low frequency of high grade adverse events. Based on this preliminary data, the authors conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial (ENGOT-OV16/NOVA) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Niraparib versus placebo, as maintenance treatment in patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer.

This study enrolled two independent cohort of patients based on the presence or absence of a germline BRCA mutation (gBRCA cohort and non-gBRCA cohort), as determined on BRACAnalysis® testing (Myriad Genetics). All enrolled patients had tumors sensitive to platinum-based therapy and had received at least 2 lines of therapy. Enrolled patients (N=553) were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive Niraparib 300 mg or placebo once daily. The gBRCA cohort included 203 patients (138 assigned to Niraparib and 65 to placebo) and the non-gBRCA cohort included 350 patients (234 assigned to Niraparib and 116 to placebo). The Primary end point was Progression Free Survival (PFS) and Secondary end points included chemotherapy-free interval, time to first subsequent therapy, Overall Survival and safety.

It was noted that patients in the Niraparib group had a significantly longer Progression Free Survival compared to those in the placebo group. In the gBRCA cohort, the PFS with Niraparib compared to placebo was 21.0 vs. 5.5 months (HR=0.27), in the non-gBRCA cohort for patients who had tumors with Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD), the PFS was 12.9 months vs. 3.8 months (HR=0.38) and for the overall non-gBRCA cohort, the PFS was 9.3 months vs. 3.9 months (HR=0.45). The P value was significant for all three comparisons (P<0.001). The most common grade 3 or 4 toxicities in the Niraparib group were thrombocytopenia (34%), anemia (25%), and neutropenia (20%), and this was managed with dose modifications.

The authors concluded that among patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer, Niraparib significantly prolonged Progression Free Survival compared to placebo and this benefit was achieved regardless of the presence or absence of gBRCA mutations or HRD status, with acceptable toxicities. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, et al. N Engl J Med 375:2154-2164, 2016