SUMMARY: It has been estimated that in the United States, 3-4% of all cancer deaths are attributable to drinking alcohol. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 88,000 deaths were attributed to excessive alcohol use in the United States between 2006 and 2010. Alcohol consumption is an established risk factor for several malignancies, and is a potentially modifiable risk factor for cancer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a branch of WHO, classified alcohol as a group 1 carcinogen. The Cancer Prevention Committee of the American Society of Clinical Oncology has now provided an overview of the evidence of the links between alcohol drinking and cancer risk and cancer outcomes.

DRINKING GUIDELINES AND DEFINITIONS

The American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and US Department of Health and Human Services all recommend that men limit intake to one to two drinks per day and women to one drink per day. People who do not currently drink alcohol should not start for any reason. A standard drink is defined as one that contains roughly 14 g of pure alcohol, which is the equivalent of 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits, 5 ounces of wine or 12 ounces of regular beer. Moderate drinking is defined at up to one drink per day for women and up to 2 drinks per day for men whereas heavy drinking is defined as 8 or more drinks per week or 3 or more drinks per day for women, and as many as 15 or more drinks per week or 4 or more drinks per day for men. Hispanics and blacks have a higher risk than whites, for developing alcohol-related liver disease. Use of alcohol during childhood and adolescence is a predictor of increased risk of alcohol related disorders later in life.

ROLE OF ALCOHOL IN CARCINOGENESIS

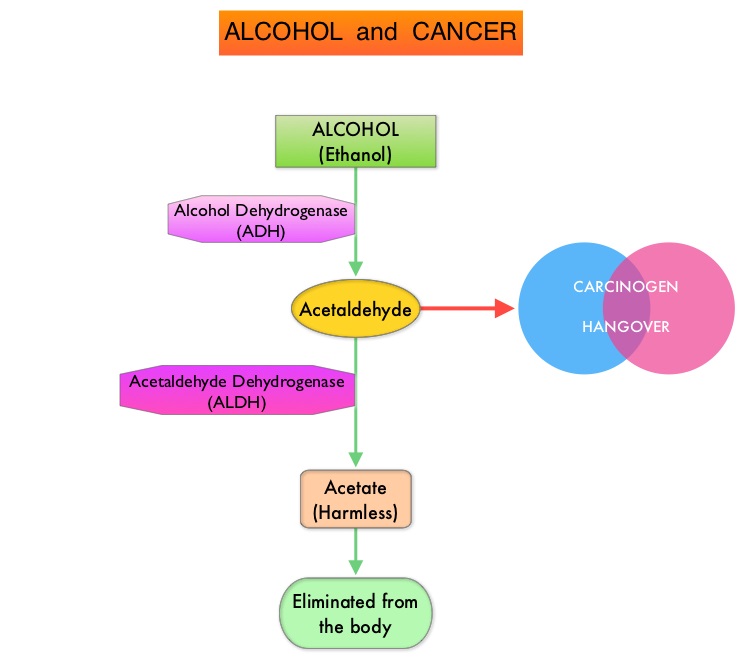

Alcohol is predominantly metabolized in the liver to acetaldehyde, which is a carcinogen and is responsible for many “hangover” symptoms. Acetaldehyde is then converted into harmless acetic acid radicals also known as acetyl radicals, and eliminated from the body. There is strong evidence to suggest that acetaldehyde damages DNA. Acetaldehyde generated during alcohol metabolism in the human body is eliminated by Aldehyde Dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2). However, a genetic variant of ALDH2, which is an inactive form, exists and individuals with the inactive form of ALDH2 who consume alcohol, accumulate excessive amounts of acetaldehyde, which in turn can lead to greater susceptibility to alcohol-induced cancer. It has been noted that this high-risk genotype in prevalent in about 50% of North East Asian population and in 5–10% of blond-haired blue-eyed people of Northern European descent. Alcohol consumption in this group is more strongly associated with cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Breast tissue is also more susceptible to alcohol than other sites. Even moderate alcohol intake has been associated with increased levels of circulating sex hormones, which in turn can activate cellular proliferation. Alcohol consumption is associated with lower serum folate concentrations and this may play a role in the etiology of colon cancer.

ALCOHOL AND CANCER

There is a clear association between alcohol and upper aerodigestive tract cancers (larynx, esophagus, and oral cavity/pharynx), as a result of direct contact of ingested alcohol with the involved tissues.

Continued alcohol use among survivors of upper aerodigestive tract cancers is associated with a 3 fold increase in the risk of a second primary tumor in the upper aerodigestive tract. Additionally, there is a synergistic interaction between alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking. Smoking and alcohol use during and after radiation therapy have been associated with an increased risk of osteoradionecrosis of the jaw, in patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancers.

Among women with Estrogen Receptor-positive breast cancer, those consuming 7 or more drinks per week have a 90% increased risk of asynchronous contralateral breast cancer, versus those who do not consume alcohol. It is estimated that there is a 5% increase in premenopausal breast cancer per 10 grams of ethanol consumed per day and the risk is even greater at 9%, for postmenopausal breast cancer.

A recent meta-analysis of cohort studies among 209,597 cancer survivors showed an 8% increase in overall mortality and a 17% increased risk for recurrence in the highest versus lowest alcohol consumers and these numbers were statistically significant.

The benefit of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular health likely has been overstated and nondrinkers have lower rates of coronary heart disease and stroke than even light drinkers. Given the increase in the risk of cancer even with low levels of alcohol consumption, the net effect of alcohol is harmful. Alcohol consumption should therefore not be recommended to prevent cardiovascular disease or all-cause mortality.

In conclusion, alcohol is a well-established risk factor for the development of certain cancers and further research is needed to understand the effects of alcohol exposure on the efficacy of chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation treatment. Alcohol and Cancer: A Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. LoConte NK, Brewster AM, Kaur JS, et al. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.1155 Journal of Clinical Oncology – published online before print November 7, 2017